Understanding Picasso's Ceramics

Picasso’s pictorial work is some of the most famous in the world. The artist, extremely prolific, has changed the history of art. It is said that there is a before and after Picasso… But do you know the full extent of his œuvre? Between 1947 and 1971, the undisputed master of Cubism created numerous ceramics, unknown to the general public. Together, let’s discover a mysterious part of Pablo Picasso’s career.

The artistic zeal

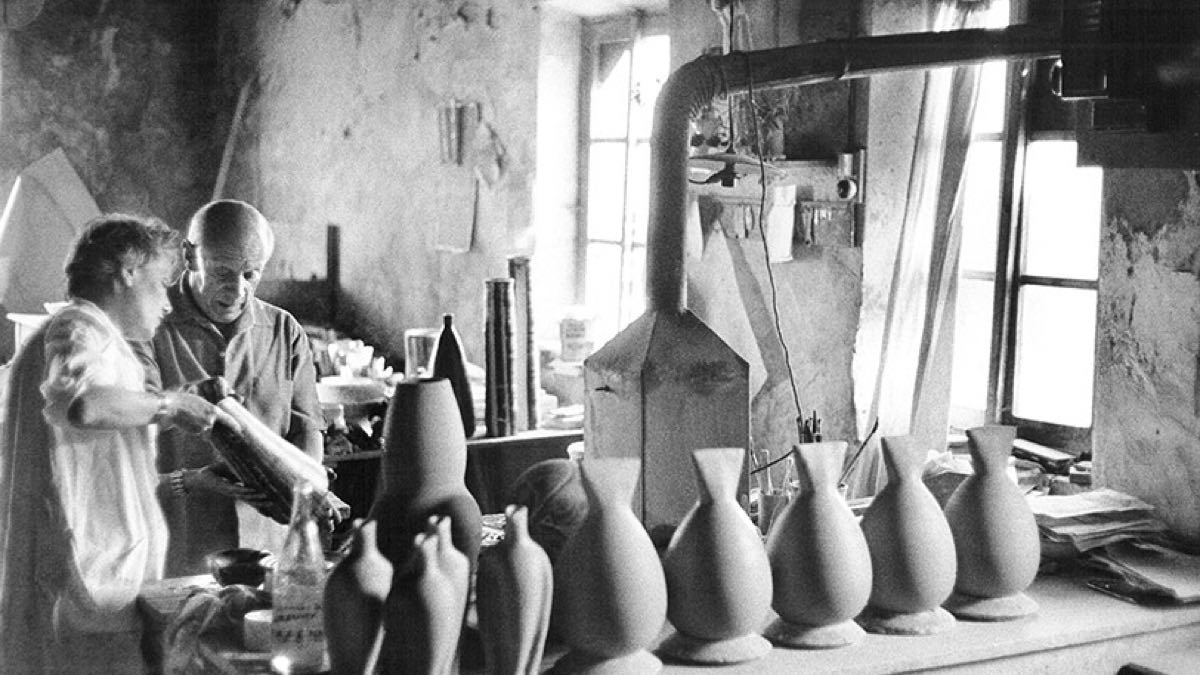

After the French Liberation, Picasso gradually spent more time in the south of France. There, he reconnected with his Mediterranean roots, and surrounded himself with famous artists of the time. He even visited Henri Matisse in Nice. The French Riviera became his playground when, in the summer of 1946, he went to a pottery exhibition in Vallauris, near Cannes. It was there that he discovered and marveled at the work of Georges and Suzanne Ramié, owners of the Madoura pottery workshop. Thus, the three artists met. A proposal followed: To create three pieces in terracotta, at Madoura. Picasso accepted the invitation and rediscovered the sensations of working with clay. Indeed, his initiation to modeling with Francisco Durrieu dated back to the 1900s…

The following year, finally settled in the South of France, the Cubist visited his ceramicist friends again. At the Vallauris workshop, he discovered the spectacular rendering of the pieces he had sent to the firing months before; it was love at first sight. Over the next two decades, Picasso explored ceramics, drawing inspiration from the light and from the Mediterranean nature.

Partnering with the Madoura Factory

With an overflowing portfolio of sketches, Picasso reworked his drawings and modeled piece after piece. This almost industrial production is reminiscent of his image as a highly prolific artist. A large number of ceramics are the result of Picasso’s creative impulse during his twenty-five years at Madoura. Vallauris allowed him to reclaim the art of clay. After the horrors of the war, the pottery studio opened the field of possibilities for the artist.

Installed in a corner of the studio specially designed for him, Picasso celebrated the power of clay. He even worked with scraps, unusable pieces of clay that no one wanted. The artist drew original shapes and painted on more traditional pieces. He would sometimes add the Picasso touch to pots created by Suzanne Ramié. She shared with him her secrets about firing the clay and painting the glaze. The residents of the workshop accompanied the artist in his creative process and paid particular attention to his personal fulfillment. They advised and assisted him in the creation of his pieces. This close collaboration has resulted in a vast collection of limited edition pots.

The goal for the group was to produce exceptional pieces at affordable prices. Picasso believed that ceramics should be considered as part of the fine arts. At the same time, it had to break with the tradition of utilitarian objects. According to Éric Moinet, the artist’s ceramics constitute “a very important part of his work that must be re-evaluated”. Long in the hands of the Picasso family, “these were pieces that were rarely seen,” especially since the French public tended to equate ceramics with a decorative art.

Adapting to a shared creative space

Other French artists known mainly for their paintings were made the guests of Suzanne and Georges Ramié. Among them, Henri Matisse, Marc Chagall and Victor Brauner. But this experience at the Madoura studio turned out to be not only professional… In 1953, the most French of Spaniards met Jacqueline Roque, his last wife. The woman who accompanied Picasso at the end of his life shared the daily life of an artist for whom ceramics was an almost spiritual retreat from the demands and worries of painting.

Embracing Mediterranean influences

Corrida Soleil, 1953 © Tajan

Among the favorite themes in the ceramics of the great Andalusian master, the spectator finds the elements of his youth between Malaga and Barcelona. On his typical Mediterranean dishes, he painted the sun, the corrida, the bulls, the birds, the tormented faces. These long years spent uprooted caught up with him. So he took refuge in his art and infused a Mediterranean aesthetic, a kind of “joie de vivre”, into his works. The Cypriot pots inspired him, he adorned them with female faces. He rendered scenes of corrida on his pots, sometimes round, sometimes oval. He was influenced by Hispano-Moorish ceramics and produced dishes and other items decorated on both sides, as were those he observed as a child.

In ceramics, the creative process subtly reflects the course of human life. Picasso was well aware of this. Clay, fire, pot. The material goes through precise cycles, which however leave a great place to chance. This allegorical dimension is expressed in his use of mythological figures, and by a recourse to pictorial elements of Antiquity. He saw this as a way of expressing the eternal conflict between mortals and immortals, between life and death.

Staying true to his Communist beliefs, Picasso depicted doves on his ceramics. At the time, returning to Spain was unthinkable for the artist while General Franco was in power. Moreover, his political commitment encouraged him to offer his pieces at affordable prices.

How Picasso’s ceramics fit in his overall œuvre

The versatility of clay opened the way for Picasso to new plastic approaches. Éric Moinet testifies: “He had a considerable influence on the work of ceramists from the 1950s to the 1970s” and is “one of the first to inscribe ceramics in the artistic language of the second half of the 20th century.” As in painting, the artist breaks the codes and explores the textures and elements, including fire and its unpredictability. But don’t be fooled, the artist does not break with his first love, painting. In 1957, 10 years after his discovery of clay, he famously reinterpreted Diego Velázquez’s masterpiece, Las Meninas.

Also, in many of Picasso’s ceramics, one can find the elements to which the artist has accustomed the viewer in painting. This is notably the case with Face no. 192, a plate decorated with a female face, that echoes his oil paintings. By practicing ceramics, the Spanish artist reconnected with his childhood soul and discovered a new passion. In fact, the artist was building an escape; he devoted the same creative process to this unexpected practice as he did to his paintings.

With the help of the Madoura factory, Picasso re-edited 633 of his ceramics. To do so, he gave instructions on the number of prints to produce. Better still, he stamped some of them with the words “original print of Picasso”. Indeed, the artist was almost religious about his pieces being signed, numbered, dated, and sometimes even located. However, Picasso intended for his terracotta pieces to be used on a daily basis. He wrote to André Malraux on this subject: “I made plates, you can eat on them”.

And today?

Today, Picasso’s signature clay works are increasingly gaining popularity. Dedicated exhibitions are emerging, such as “Picasso ceramist and the Mediterranean” in 2014 at the Centre d’art des pénitents noirs in Aubagne or more recently “Picasso-Rodin” at the Picasso Museum in Paris. In addition, the research around the work of the monument of modern art continues to deepen. On the art market, his ceramics are regularly put up for auction. Recently, Christie’s set a sales record with Grand vase aux femmes voilées, sold for 1.14 million euros. Pablo Picasso’s story is an eternal source of inspiration for his successors. It is now the subject of numerous studies, in the light of contemporary societal issues.

About Artsper

Founded in 2013, Artsper is an online marketplace for contemporary art. Partnering with 1,800 professional art galleries around the world, it makes discovering and acquiring art accessible to all.

Learn more