Why Are Marble Sculptures So Popular?

It may be the works of Greek and Roman Antiquity that come to mind when you first think of marble sculpture. However, the unique properties of this metamorphic rock have led to it transcending the millennia as it continues to dominate the art scene as one of the leading sculptural mediums today. What is it about this opulent stone that sculptors across the ages have been so unable to resist? Why marble, as opposed to carved wood, fired clay or cast bronze? Join Artsper, as we travel through time to explore the appeal of marble sculptures.

What makes marble so unique?

Marble is a tale of two stones. Although famous for its extreme durability, when first quarried, it is soft and malleable. It is only with time that its hardened exterior forms. Sculptors are therefore able to chisel it in almost any way they wish. Its fine grain similarly enables sculptors to craft the characteristic minute detail of marble sculptures. However, it is undoubtedly its ability to absorb a small amount of light before refracting it, that distinguishes marble from similar rocks. This creates the soft, translucent effect which allows it to appear simultaneously as stone and as skin. Michelangelo no doubt took a different approach during the Renaissance than Roland Masson does today. However, it is clear that the unique properties of marble have exerted their pull on generations of sculptors. With this in mind, let’s discover the popularity of marble sculptures through the ages!

Why was Classical Antiquity so obsessed with marble?

From the works of Phidias and Polykleitos, to the Trajan Column and Augustus of Prima Porto, the world of Classical Antiquity had an abundance of the finest marble sculptures. However, in an art scene dominated by pottery, painting and architecture, how did marble become the sculpting medium par excellence?

Marble first rose to prominence in Greece’s Classical period (500 BCE to 323 BCE). Its natural properties represented the opportunity to portray the human forms of their Gods in naturalist detail. As a result, this period saw a great refinement in chiseling techniques, many of which were then exported to Ancient Rome. Here, sculptors sought a similar degree of detail to the Greek naturalists, however, the sculptures served a different purpose. As Daniel Boorstin writes in The Creators, “while the Greeks had given their gods an ideal human form, the Romans strived to make their rulers godlike.” Busts and copies of Greek bronzes were therefore used to adorn the capitals of columns and to represent heroes, emperors, generals and politicians. Marble sculptures were, in many ways, used as a tool to keep track of who was in power and of the trends of the day.

Thus, the Romans preferred to use sculpture to edify individuals, while the Greeks focused on realizing their Gods. It is therefore clear that the purpose marble served differed across the two societies. However, their passion for marble created an all important continuity across Antiquity and testifies to its popularity.

How did the love affair with marble continue into the Renaissance?

The use of marble persisted throughout the Middle Ages. Despite a detour from the naturalism of Antiquity, the sculptors of the Medieval period still chose to use marble to create their stylized depictions of religious scenes. However, it was in the Renaissance that artists and sculptors alike revived an interest in Classical art, naturalism, and, of course, marble.

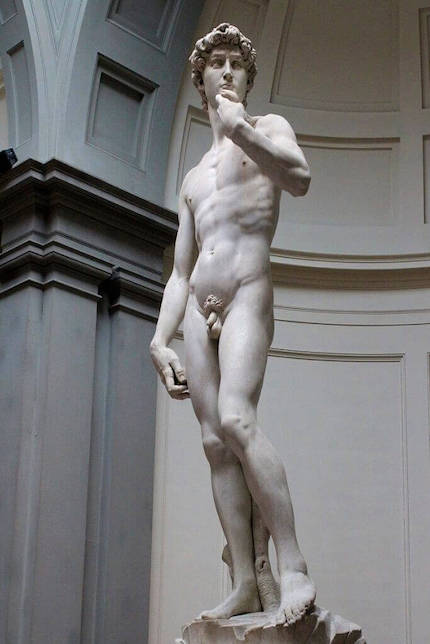

It was during this period that many of the most famous sculptures were created, among them, Michelangelo’s David and his Pietà of St. Peter’s Basilica. Michelangelo was one of the major proponents of classicism in the Renaissance. It is therefore of particular significance that the natural properties of marble seem to have appealed to him in the same way as they did to the Greeks and Romans. He himself declared his role as an artist “to liberate the human form trapped inside the block by gradually chipping away at the stone surface.” Michelangelo thus found himself seduced by the possibility of using the luminosity, elegance and timelessness of Carrara marble to represent skin. As sculptors across the Renaissance turned to marble for this very same reason, the stone remained a staple of artistic culture throughout the period.

Did marble sculpture survive the avant-garde revolution?

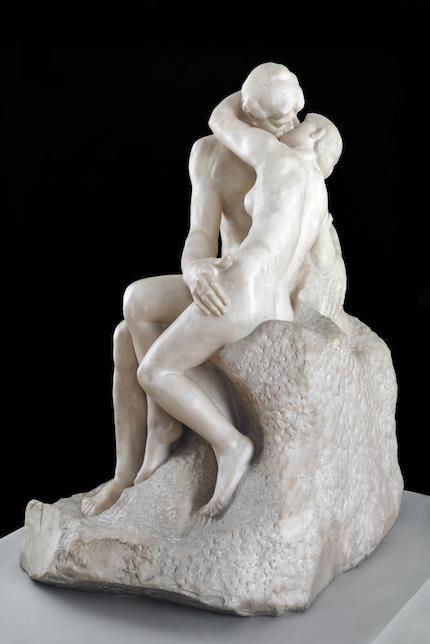

Let’s skip to the mid-19th century. The foundations of modern art are being set. Artists are rejecting the tyranny of academia. The desire to explore specific subjectivities is rife. Marble sculpture is no exception to this. The French sculptor, Auguste Rodin, pulled the art out of the semi-obscurity into which it had fallen over the past two centuries. He used traditional techniques, learned from Michelangelo, and adapted them to create models which are emotive rather than directly figurative. After dabbling in other sculptural mediums, Rodin turned to marble to convey this emotion. By illuminating the sculptures from the rear, he would cause them to glow with the intensity of their passion. This technique is clearest in his masterpiece The Kiss.

However, at the beginning of the twentieth century, a seismic shift took place: the avant-garde. Gone were the days of figurative representations of bodies in marble sculpture. Constanin Brancusi emerged as a force to be reckoned with, rejecting the school of thought surrounding Rodin. He instead focussed on the body’s mystical inner core, abstraction and primitive motifs. A far cry from the naturalism of Antiquity or Michelangelo. By exploiting the natural properties of marble, Brancusi challenged the viewer to reflect upon what sculpture actually was. As other sculptors similarly re-evaluated the uses of marble in their work, the popularity of marble persisted. Yet it emerged from avant-garde wholly transformed.

In a world of Pop Art and visual culture, does marble sculpture still hold a place today?

Following the innovations of the avant-garde, artists of the 21st century are continually reconsidering marble sculptures. Not only does this stone carry its wealth of natural properties, it also bears the weight of millennia of history and artistic tradition. The up-and-coming sculptors of today have been playing with this and questioning the conventions of days gone by in their effort to create truly innovative work. Among them is Massimiliano Pelletti, who attempts to maintain his ties to traditional sculpture by using classical molds, while also seeking to innovate as he uses unconventional kinds of marble. Patricia Guinois Messica similarly integrates old and new in her works. Although she explores age-old themes, including femininity, motherhood, and movement, she does so in an untraditional way as she allows the stone to reveal its soul and form, thus becoming one with the stone.

Marble has transcended the ages. It has taken different forms, held varying purposes and inspired generations of sculptors in countless ways. However, what has remained constant across the millennia, is this stone’s unique ability to appear simultaneously as living and inanimate. The popularity of marble all links back to this tale of two stones. Durable yet soft. Light yet heavy. Stone and yet still skin.

About Artsper

Founded in 2013, Artsper is an online marketplace for contemporary art. Partnering with 1,800 professional art galleries around the world, it makes discovering and acquiring art accessible to all.

Learn more