Sculpture and Allegory

Sculpture and allegory are theoretical concepts of the same design. One could go as far as to say that sculpture is founded in allegory. The functionality of sculpture must be first decided upon. Designed not with the purpose of functional value such as a chair intended for sitting, sculpture is designed to convey meaning through aesthetic beauty. Art is wrongly perceived as 2-dimensional sometimes. There is the physical and the meaning it infers as well as the third dimension of meaning it. That meaning relating to a less literal narrative- a narrative of another world, of the past or imaginary.

The medium of sculpture

It must be reminded that all conversation surrounding sculpture and allegory comes in the legacy of Craig Owens’ book. The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism published in 1980 proved enlightening on the subject. Allegorical artworks go further than conveying beauty through meaning but rather rely on a nuance of signification. The observer is able to pick up upon in a web of meaning conveyed by the artist. An analysis of allegory, sculpture, poetry, signification and nuance will provide the basis of this following discussion. We will explore the work of Damien Hirst, Pablo Picasso, Auguste Rodin, Arman and many other allegorical abstract figurative sculpturists.

To introduce the conversation here is S. T. Coleridge’s famous condemnation of allegory, “It makes a great difference whether the poet starts with a universal idea and then looks for suitable particulars, or beholds the universal in the particular. The former method produces allegory, where the particular has status merely as an instance, an example of the universal. The latter, by contrast, is what reveals poetry in its true nature: it speaks forth a particular in its living character; it implicitly apprehends the universal along with it.” —Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Coleridge’s miscellaneous Criticism, p.99

What is allegory?

As a literary device or art form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation that can be interpreted to represent a hidden significance. Throughout history, authors have used allegory in all art forms. They have used it to illustrate complex ideas in ways that are thought-provoking to their audience. Many allegories use the personification of abstract concepts.

The roots of allegory in art

Sculpture is the perfect medium for the exploration of allegory. Within Western culture, written forms of allegory in literature have originated from biblical roots. Beyond that of the religious allegory are the closely intertwined concepts of myth and allegory in art. Another dimension to allegory exists in the study of psychoanalysis in art. Many theorists have explored the subject of the human psyche and what allegory in art can reveal about it.

Some of the earliest allegories are found in the Hebrew Bible. This includes the metaphor in Psalm 80 of the vine’s impressive growth representing Israel’s conquest of the Promised Land. Allegorical interpretation of the Bible was a common practice among early Christians and continues. This allegorical decoding of the religious message in a parable can be related to the unpacking of religious imagery.

Allegory in art is when the subject of the artwork is used to symbolize a deeper moral or spiritual meaning. This can take on the appearance of subjects such as life, death, love, virtue, justice etc. An example of which is a statue of Lady Justice represents justice, traditionally holding scales and a sword.

Classical allegory

The origins of allegory can be traced at least back to Homer in his “quasi-allegorical” use of personifications of Terror (Deimos) and Fear (Phobos). The unstable nature of this as quasi-allegory comes down to the distinction between two often conflated uses of the Greek verb “allēgoreīn,” which can mean both “to speak allegorically” and “to interpret allegorically.”

Theagenes is the earliest case of interpreting allegorically. Presumably in response to proto-philosophical moral critiques of Homer, Theagenes proposed symbolic interpretations whereby the Gods of the Iliad actually stood for physical elements. So, Hephestus represents Fire, for instance. One of the best-known allegories in classical literature is the Cave in Plato’s Republic (Book VII) .

Plato’s Cave

Among the best-known examples of allegory is Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. The story forms a part of his larger work The Republic. In the Cave allegory, Plato describes a group of people who have lived chained in a cave for the entirety of their lives. The people watch shadows on the wall projected by figures passing a fire behind them and begin to identify to these shadows, using language to clarify their world.

According to the allegory, the shadows are as close as the prisoners get to viewing reality, until one of them finds his way into the outside world where he sees the actual objects that produced the shadows. The prisoner tries to tell the others in the cave of his discovery, but he is not believed and the others resist his efforts to free them. At its core, the allegory is about a philosopher who thinks it is his duty to share knowledge upon its discovery (outside the cave of human understanding), and the foolishness of the other prisoners think of themselves as fully enlightened and therefore ignore the philosopher.

Medieval and modern allegory

Lady Justice is perhaps the most common example of allegory in modern sculpture. This approach of uses the human form and its posture, gestures, clothing and accessories to wordlessly convey social values and themes. Lady Justice can be seen in funerary art. She also appeared on Renaissance monuments when patron saints became unacceptable. The four cardinal virtues and the three Christian virtues were particularly popular, but other themes such as glory, victory, hope and time are also represented. The use of allegorical sculpture was fully developed under the École des Beaux-Arts, a number of influential art schools in France that date back to the 19th century.

Auguste Rodin

Rodin is perhaps the most well-known sculptor out of the artists on this list. Nethertheless, his sketches prove illuminating on the subject of allegory. An example of which is the sketch, Allegory of Spring, 1882–1888. In the late 19th century, Auguste Rodin developed a radical new approach to his medium. He primarily created organic and textured forms that broke away from the classically idealized, mythological sculptures of the past. Working with many formats from bronze to marble to terracotta, his works detail singular figures, lovers, and even group scenes. In his most famous works, including The Thinker, Rodin shaped bodies that convey significant emotion, from mental anguish to desire. This is done via details such as furrowed brows, hunched back muscles, and suggestions of touch.

Rodin’s The Gates of Hell

In 1880 Rodin was commissioned to create a pair of bronze doors for a new decorative arts museum in Paris. The result? The Gates of Hell, a defining project of Rodin’s career. For over 37 years, Rodin sculpted, removed, or altered the 200+ figures on the doors. Some of his most famous works, like The Thinker, The Three Shades, or The Kiss, were originally conceived as part of The Gates and were only later removed, enlarged, and cast as independent pieces.

Rodin’s initial inspiration came from Inferno (Italian for “hell”), the first installation of Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s (1265–1324) epic poem The Divine Comedy. It is believed that Rodin saw the scenes described by Dante as a void, allowing for neverending figurative experimentation. Rodin could play with the sculpted poses, gestures, and even sexuality. The chaotic population on The Gates of Hell express their agony ceaselessly. In the end, the artist discarded the specific narratives of Dante’s poem.

Today, the work is much more than an interpretation of Inferno. Rather, the doors evoke universal human emotions and experiences. These include forbidden love, punishment, and suffering, but they also suggest unapologetic sexuality, maternal love, and contemplation. In Rodin’s lifetime The Gates of Hell was never cast in bronze. In spite of this, the sculpture’s allegorical value remains intrinsic to its legacy as Rodin’s most well-known sculpture.

Pablo Picasso

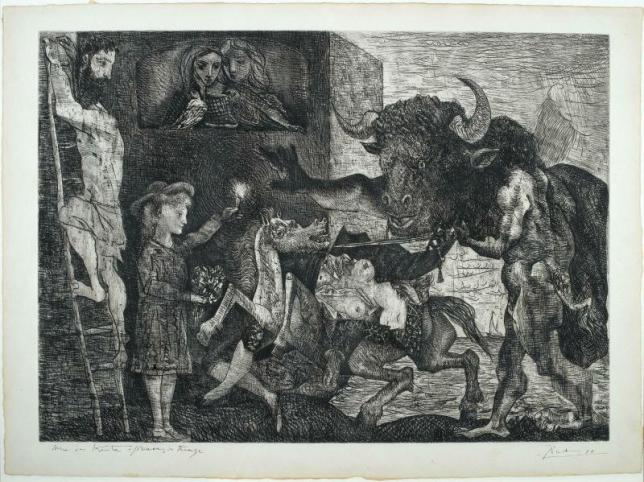

Despite it not being a sculpture, La Minotauromachie deserves to be noted in this essay upon allegory. This is because of its rapport to Picasso’s allegorical sculptural works during a period in the Parisian-situated part of his career in 1935. La Minotauromachie is an absolute masterpiece of etching and engraving. Executed in the early months of Marie-Thérèse Walter’s pregnancy, it annonces allegory that interweaves the world of bullfighting with a mythological fable.

“Every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably”. —Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History

“Anything that comes to hand can be distorted from its customary use, and what the artist uses it for calls into question the use-values of any object. […] As if, in Picasso’s daily life, in objective reality and in the use-value of objects, there were metamorphoses of this kind lurking.” —Werner Spies et Christine Piot, Picasso: the sculptures, Ostfildern-Ruit/ Hatje Cantz, 2000

At the center of the composition lies a pregnant and wounded female matador. She is supported by a disemboweled horse, representing a possible symbol of the tragic end of the painter’s marriage to Olga, from whom he separates a few weeks later. With Picasso-as-Minotaur groping towards her, Marie-Thérèse – an allegory of hope and a symbol of serenity for the artist- appears a second time in the form of a young woman holding a bouquet of flowers and lighting the dramatic scene with a candle. This artwork inspired many of Picasso’s further sculptures with its mythical quality held as a running thread of the artwork of this period in his career. La Minotauromachie inspired the sculpture of the female goat seen below.

Picasso’s Goat

From 1948 onwards, Picasso’s studio in the town of Vallauris was situated next to a pottery yard. Picasso searched the yard for discarded materials that could suggest parts of the animal’s body. From there, he created a makeshift skeleton with his found objects, and filled out the sculpture with plaster. A wicker basket forms the goat’s rib cage; two ceramic jugs were modified to serve as its udders.

Allegory in contemporary sculpture

Verity, 2012 is a stainless steel and bronze statue created by Damien Hirst. The 20.25 meter high sculpture stands on the pier at the entrance to Ilfracombe Harbour. It was on loan to the city for 20 years. The name of the work refers to the notion of truth. Hirst describes his work as a “modern allegory of truth and justice.”

Hirst is one of the many contemporary artists relying on a rich history of allegory in the realm of sculpture in his contemporary artwork. Now you have explored the intrinsic link between allegory, sculpture and art why not discover other contemporary sculptures inspired by allegory on Artsper!

About Artsper

Founded in 2013, Artsper is an online marketplace for contemporary art. Partnering with 1,800 professional art galleries around the world, it makes discovering and acquiring art accessible to all.

Learn more