The Canon of Proportions in Ancient Greek Sculpture: Searching for a Divine Ideal

Derived from the word “Kanôn,” which designated a measuring instrument, the canon has become synonymous with a model. As a true reference, it can concern the aesthetic, the spiritual or the intellectual. In sculpture, drawing or painting, it is still used today as a tool to represent realistic and harmonious proportions. But what rules governed this aesthetic search for perfection in ancient Greece? Artsper invites you to discover the foundations and subtleties of the canon of proportions in Greek sculpture!

Polyclitus, the inventor of the canon of proportions

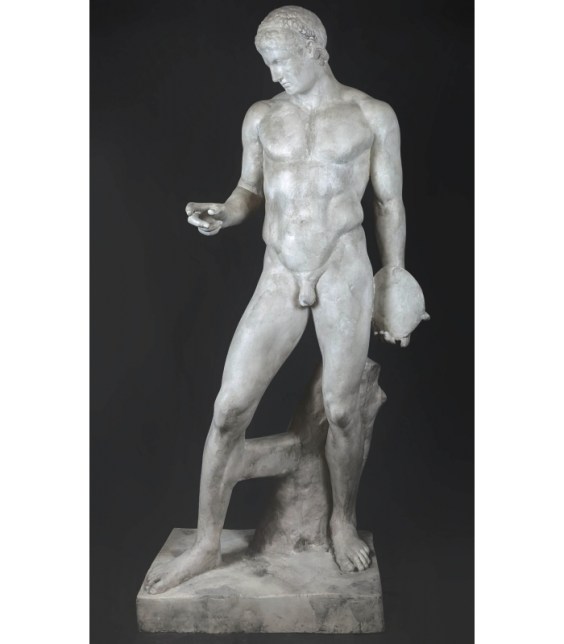

Although rules of proportion already existed, Polyclitus was the first to theorize the aesthetics of the body and the nude. In the 5th century BC, he wrote a treaty of ideal proportions called “the canon”. He revolutionized our relationship to the human body by assigning to beauty a quantifiable and numerical value. His canon is based on a fundamental rule: the balance and the ratio of proportion between the different parts of the body. Thus, beauty is based on the harmony between the different parts of the body and its whole. In other words, each part of the body must measure a certain size in relation to the total height of the body. A foot should measure a certain percentage of the whole body, as well as the head or the finger. This become a new representation of beauty based on a strict mathematical and aesthetic law.

The precise rules of the canon of proportions by Polyclitus

The canon of Polyclitus is therefore a set of rules used to create perfection of beauty of the human body. One finds very precise principles of proportion. First, the head enters 7 times in the height of the body. Then, the legs and the torso measure the same height, three times that of the head. The knees and feet are twice the height of the head, as is the width of the shoulders. This is also the case for the height of the torso. Finally, the pelvis is two-thirds the height of the torso, while the thighs are two-thirds of the legs.

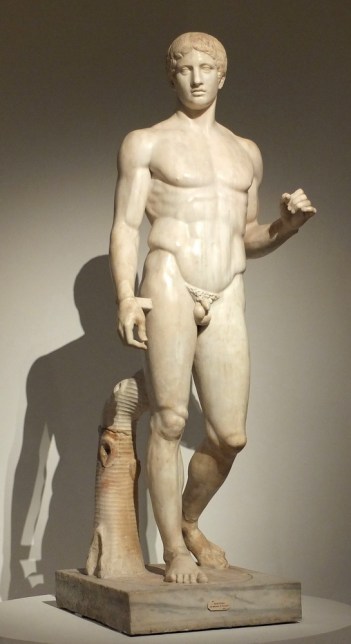

The goal of this treaty is concrete: Polyclitus intended for the canon to be used by all to serve art and representations of the beautiful. Both practitioner and theorist, Polyclitus created a sculpture that applied the rules set out in his treatise. Doryphorus, still considered today as one of the most famous and classical of sculptures.

The canons of beauty in Lysippus and Leonardo da Vinci

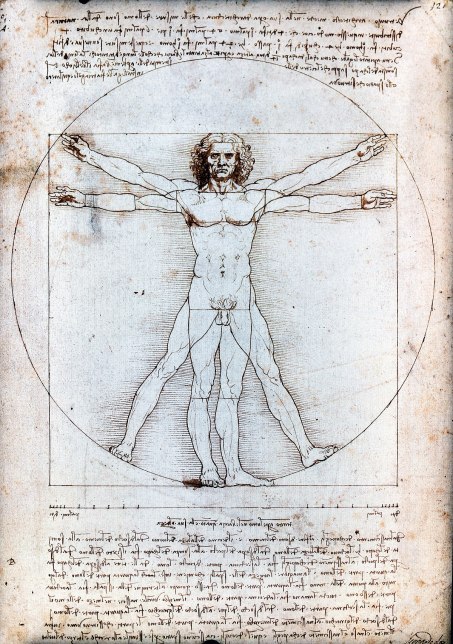

A century after Polyclitus, Lysippus revisits this canon. On a similar principle, the body becomes slenderer, the silhouette slenderer and slenderer. The body measures eight times the height of the head, against seven in the canon of Polyclète. Later on, Leonardo da Vinci used the logic of the canon of proportions to create Vitruvian Man. He also applied the golden ratio to capture his own canon of ideal, divine proportions.

But whether it is Lysippus or Leonardo da Vinci, the principle remains the same: harmony between the parts and the whole. By developing their own canon of proportions, these sculptors in fact materialize their representation of the world, based on a mathematical ideal. They demonstrate that the human body is embedded in a much larger system of function, in that of natural laws. Man holds the same place as any other form of life present in nature. He has a universal beauty, whose origin is at the same time divine, mathematical and perfect.

Is the canon of proportions reductive?

But can we really quantify, mathematize and proportion beauty? If many artists have tried to set up rules of absolute beauty, the reality seems quite different. To consider beauty as universal and objective is to deny the very foundation of beauty. Because if we know today that symmetry is pleasant to look at, beauty is anything but immutable. On the contrary, its perception changes according to geographical, cultural and subjective factors. As the saying goes, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.”

About Artsper

Founded in 2013, Artsper is an online marketplace for contemporary art. Partnering with 1,800 professional art galleries around the world, it makes discovering and acquiring art accessible to all.

Learn more