Bewitched! Women as Witches in Art History

Artsper is taking a look at art history through the lens of the supernatural. As long as superstition has existed, it has appeared in artwork – a testimony to both our fear and curiosity for it. One of the more thought-provoking areas of this topic is the portrayal of Witch Art.

Witch art sheds light on the ostracization and oppression of women throughout history. Those outcast women unfortunate enough to be accused of witchcraft have both fascinated and frightened artists. A combination of fear and an age-old predilection for the superstitious has birthed incredible imaginative interpretations of the occult. A retrospective look back at witches in art reveals much about society’s tragic treatment of women.

The History Behind Witch Artworks

General conjecture about the nature of witches was that they were individuals who made pacts with the Devil in exchange for supernatural powers. They would use such powers to commit sinful acts. Between the 15th and 17th century, more than 90,000 people were formally accused of witchcraft, with half of these executed. In Western Europe, the overwhelming majority of the accused were women: in England 90%, and in the Holy Roman Empire and France 76%.

But why were women villainized as witches? It is a question widely debated between historians and anthropologists. The general consensus is that women have been historically considered more susceptible to the Devil’s influence. Women had a so-called “disposition for hysteria and jealousy,” and a generally more corruptible nature.

The Rise of the Witch Hunt

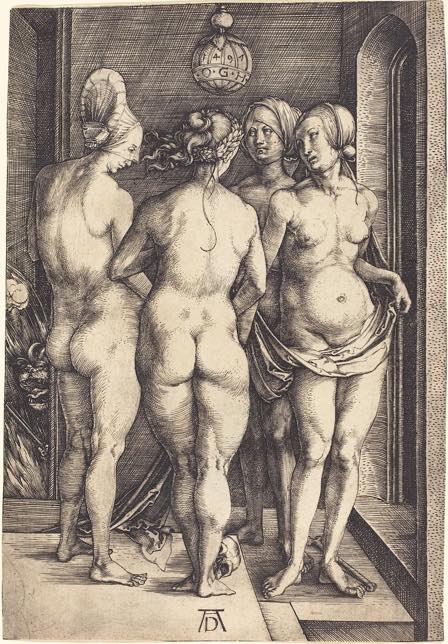

We see witch art within Western art as early as the beginning of the Dark Ages. A prominent and early example is Albrecht Dürer’s Die Vier Hexen, which translates to The Four Witches. This engraving from 1497 depicts a coven of four nude women. They are accompanied by a small horned demon to the left of the centre, an overt symbol of the Devil. Skulls and bones scattered on the floor may be a symbol of death, magic or invocation from an evil deity.

The idea that this is associated with witchcraft is further inferred from the fact that its production coincides with a highly popular but deeply misogynistic guide to witch hunting. The Malleus Maleficarum (‘The Witches Hammer’) was released for a third time the year before this engraving was made.

Magic and Hysteria

Another poignant example of witch art is Salvator Rosa’s Witches at their Incantations. Created around 1646, this painting’s creation coincides with the height of the witch mania that was spreading throughout Europe. It depicts haggard old naked women, some stooped over cauldrons, and a baby being sacrificed to skeletal, devilish monsters. The scene portrays a witches’ sabbath, a satanic inversion of a Christian mass. It’s an illustration of the fear heretics can survive undetected within a God-fearing community.

By propagating fear, the Church effectively encouraged the demonization of women who were perhaps outsiders, unmarried and vulnerable. It served as a method to quell anxiety, as well as strengthen their own hold over the community. Interestingly, whilst the artist aimed to depict the villainy and wickedness of the witches, in retrospect it demonstrates only the cruelty of the European world of the 17th century. Ironically, the society which attempts to debase women, cannot see that it is the problem itself, creating fear and suffering amongst those they persecute.

A Change in Attitude

We see a shift in this attitude towards the end of the 18th century. Francisco de Goya’s Witches’ Sabbath (1798) at first glance seems similar to Rosa and Dürer paintings. It depicts the Devil in the form of a goat surrounded by a coven of witches in a barren landscape. The witches seem to be sacrificing newborns to the devil, with the corpse of an emaciated infant discarded to the left and one infant being offered up in the forefront of the painting. Goya uses the inverted imagery associated with witchcraft: the goat extends its left rather than right hoof towards the child and the quarter moon faces out of the canvas on the top left corner.

Many art historians, however, believe the artist intended to challenge the messages seen in witch art from centuries prior. This is partly due to the number of clichés Goya includes in the painting. This is inferred as criticism of the superstition and paranoia that dominated Spain at the time. Secondly, the painting is a part of the artists Black Paintings series, in which the artist expressed his disillusion with the social and political changes happening in Spain at the time. Coinciding with the chaos caused by the Spanish Inquisition, Goya depicts a bleak vision of humanity.

Contemporary Representations

Movements in later centuries saw efforts from women to reclaim the title of witch. An age-old term of shame and stigma, feminist artists embraced the idea of witches and the occult. One of the first to do so was abstract artist and mystic Hilma af Klimt. The Swedish artist was part of a group, called the “The Five,” who attempted to contact beings called “The High Masters” through séances. Her abstract paintings, considered to be first examples of Western abstract art, are visual depictions of these spiritual interactions. In 1904 she was instructed by the spirit world to create a series of works called the Paintings of the Temple. A project that would occupy her for the next 9 years, the series was eventually installed in a spiritualist temple.

Contemporary artists are carrying on this tradition of reclaiming the term “witch” and its connotations. Liz Ophoven is a Seattle artist who draws inspiration from the spiritual, as well as traditional folklore and myth. She creates statues from clay, inspired by myth and female deities. Kayava and Nesly Richard similarly are inspired by the occult, magic and ancient voodoo traditions. Their work features many pagan-like symbols, tapping into classical depictions of sorcery and witches.

The Evolution of Witch Art

It is interesting how our relationship with the word “witch” has changed so much, and studying witch art throughout art history can help to unpack the connotations of the change. Undoubtedly this has much to do with changing societal relationships with women, as they have fought back against their systematic oppression, attempting to reclaim the term in a positive light. In turn, the term has become less of a tool of subjugation.

This is particularly true in relation to the lessening influence of establishments such as the Church. Once used to propagate fear in order to further its own political agenda, the Church no longer has such a hold over us as a collective society. Instead in the modern age it is just a playful and light-hearted term; a costume for a Halloween party or a villain in a children’s scary story. But next time you see a witch in art, remember that she is much more than a caricature, and has a long, complex history behind her…

About Artsper

Founded in 2013, Artsper is an online marketplace for contemporary art. Partnering with 1,800 professional art galleries around the world, it makes discovering and acquiring art accessible to all.

Learn more