What are the Dominant Trends in Japanese Art?

This week, Artsper takes you to the Land of the Rising Sun. Here, we are not going to talk about the cherry blossoms in Kyoto, nor the refinement of the Geishas and even less about the best way to place the seaweed leaf when making your maki. Rather, let’s take a journey through time, to discover the dominant trends in Japanese art.

The Ancient

The Oldest Metallic and Ceramic Production from the Yayoi period (ca. 300 BC – ca. 300 AD).

The Yayoi era, which dates from approximately 300 BC, is an incredibly rich period of production in the history of Japan and the first of the most dominant trends in Japanese art. First, it corresponded to the golden age of bronze and iron (discovered simultaneously!). It also coincided with the beginnings of rice growing. The residences then regrouped in the form of real villages, making metallurgy and ceramics, essential techniques of life in the countryside. Consequently, many swords and other defenses are produced, but also the Dōtaku, bell-shaped objects, melted in fine bronze. Decorated with hunting scenes or mostly geometric shapes, the Dōtaku are associated with agrarian rites.

Additionally, ceramics saw the birth in particular of the Kamekans, jars-coffins placed in funeral fields, and were intended to accommodate the bodies of the deceased. The luckiest, and consequently the highest placed in the social hierarchy, are sometimes accompanied in the afterlife with small bronze objects.

Kofun funeral art (300-710)

The Kofun period (300-710), also known as the “Era of the Great Burials”, followed the Yayoi era. The art of this era revolved around two main types of production. First, the Kofuns, bearing the same name as the time in which they appeared. The monumental funeral architectures were intended to welcome and celebrate important figures, such as emperors or village chiefs. The best known Kofun is Emperor Nintoku, who according to legend, lived for no less than 109 years (290-399). These large mounds generally take shape in circular, lock, or scallop forms. At the beginning of the 6th century, funerary paintings appeared within the mounds. With time the depictions became increasingly realistic. According to some art historians, this notably marked the origins of Japanese painting.

The second major type of production from the Kofun period was closely linked to these monumental tombs since they are funerary statues. These terracotta statuettes, called Haniwa, take various forms ranging from the representation of man (dancers, servants) to animals (dogs, wild boars). They are used to accompany the dead in their passage between the two worlds. To see Haniwa in the flesh, be sure to head to the Guimet Museum in Paris!

The Classics

Buddhism in Nara (710-793)

The Nara period (710-793) takes its name from the city of Nara, Japan’s former capital. As a city of art and history, it has a multitude of UNESCO world heritage sites.

The Nara era was a period of transition for the country, which fully applied the Ritsuryo (meaning “Chinese system”) both to its political organization and its artistic production. The arts had been flooded by the influence of the Tangs; particularly in architecture, which had experienced a real boom. It was during this period where there was a significant proliferation of Buddhist temples and monasteries. One such temple was the Kofuku-Ji, built in 710.

Sculpture also experienced a remarkable development, with the rise of two new techniques. The techniques included hollow dry lacquer, a complex and expensive technique, and dried earth, which was defined by a clear search for realism.

In the field of painting, the impact of Chinese culture was illustrated through the physical aspect of the painted figures. The figure of Kichijoten is particularly representative of this influence: a Japanese deity, however depicted with a babyface, adorned with arched eyebrows and a delicate red mouth, which, like the patterns on his clothes, refer to Chinese art.

The Refinement of the Heian era (794-1185)

The artistic production of the Heian period (794-1185), unlike that which appeared during the Nara period, was characterized by its distinctly Japanese identity. This independence from Chinese art was first noticed by the emergence of the Japanese syllabary. Given the name Kana, it allowed for the development of new literary forms, such as court novels or Monogatari (poetic tales).

Furthermore, the birth of characteristic painting arose in the Yamato-e style (“Japanese painting”). Contrary to Chinese painting, the Yamato-e refused the representation of theatrics in favor of rural scenes, highlighting the landscape and the daily life of peasants. This style of painting, rich with color, frequently used sliding doors and scrolls as mediums. Some patterns are recurring, including the strip of clouds above the characters’ actions.

The Most Famous

Edo Erotic Prints (1618-1694)

The Edo period is without doubt the most famous amongst Western countries. This period saw the development of the pictorial movement of the Ukiyo-e (“images of the floating world”), known for its prints. The art of printmaking had widely spread throughout Europe, thanks to the notable work of Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), who painted the 36 views of Mount Fuji, the most famous being The Great Wave. Artists had to master a number of demanding techniques where it took the work of several people to simultaneously draw, engrave, transfer, print, and publish the work.

The themes found in the productions of the Edo period correspond to a particular change in Japanese society, which had become predominantly urban. At the same time, numerous brothels were opening and the notion of pleasure occupied an essential place for the new bourgeois social class. Ukiyo-e’s tendency to offer a hedonistic view of life quickly became pornographic art (therefore laying the foundations of Hentai).

The Most Modern

The Dynamism of the Meiji Era (1868-1912)

The Japanese cultural field experienced exceptional growth during the Meiji era (1868-1912) thanks to the modernization and globalization of its production and artistic techniques. By giving others access to their land, Japan experienced a decline of tradition (ie. the wearing of the Kimono) but also gained unprecedented success in their techniques, such as ceramics or lacquers. As a result, two dominant trends emerged during this period. On the one hand, the defense of modernity with teaching in the academies of Yō-ga, Japanese painting in Western-style. On the other, the continuation of traditional techniques of the peninsula, with the teaching of Nihonga (“Japanese painting”), a synthesis of the various ancestral artistic traditions. During this period, Japanese art was particularly promoted through the organization of the first universal exhibition, showcasing its true power.

Today in Modern Japan

Today, there is divide between artists who preserve the artistic traditions of Japan, and those who detach themselves from it to offer something innovative, both offering dominant trends in Japanese art. Sometimes artists practice both at the same time.

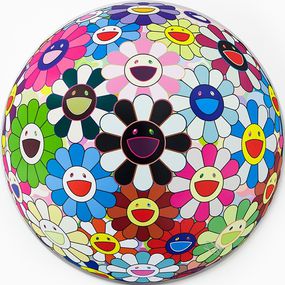

Since the 1990s, a time of crisis for the country, the West had the tendency to reduce contemporary Japanese art to the Superflat movement. The term was popularized by one of the major figures in the country’s art scene, Takashi Murakami. The artist is known for his colorful and flowery paintings inspired by Japanese pop culture. Also in a derivative way, Yayoi Kusama influenced it, known for her psychedelic works with polka dots.

However, today’s Japanese art scene should not be limited to that, nor to manga or anime. For example, have you ever heard of Gutai art (“concrete art”), the founding movement of Japanese contemporary art? For example, Shozo Shimamoto leaves his works to chance. This notion inspired other artists, such as Pierre Soulages, master of “Black Light”. Perhaps you also know the Metabolist movement? If not, take a look at Kurokawa Kishô’s organic form architecture (1934 – 2007).

Japanese contemporary art is multifaceted and rich. Now more than ever, Japanese artists conquer their ancestors’ identity questions. Through painting, sculpture, installation, and even video, they continue to draw inspiration from the state of the world today.

About Artsper

Founded in 2013, Artsper is an online marketplace for contemporary art. Partnering with 1,800 professional art galleries around the world, it makes discovering and acquiring art accessible to all.

Learn more