Street Art and The City

Although the street art movement officially began in 1960s Philadelphia, art itself quite literally began in the prehistoric “streets” of Indonesia. Figurative images of animals were painted across walls, identifying and marking ancient communities.

Like art, revolutions also began in the streets where the urban backdrop provided the means to unite individuals and voice their desires for change. Over time, however, artistic expression has become increasingly restricted where prestigious art schools, opulent galleries and extravagant auctions are reserved for the privileged. This is why street art’s presence is so important in our cities: it is not highfalutin, it is accessible by all, and as a result has left a considerable stencil-shaped mark on the almighty art world.

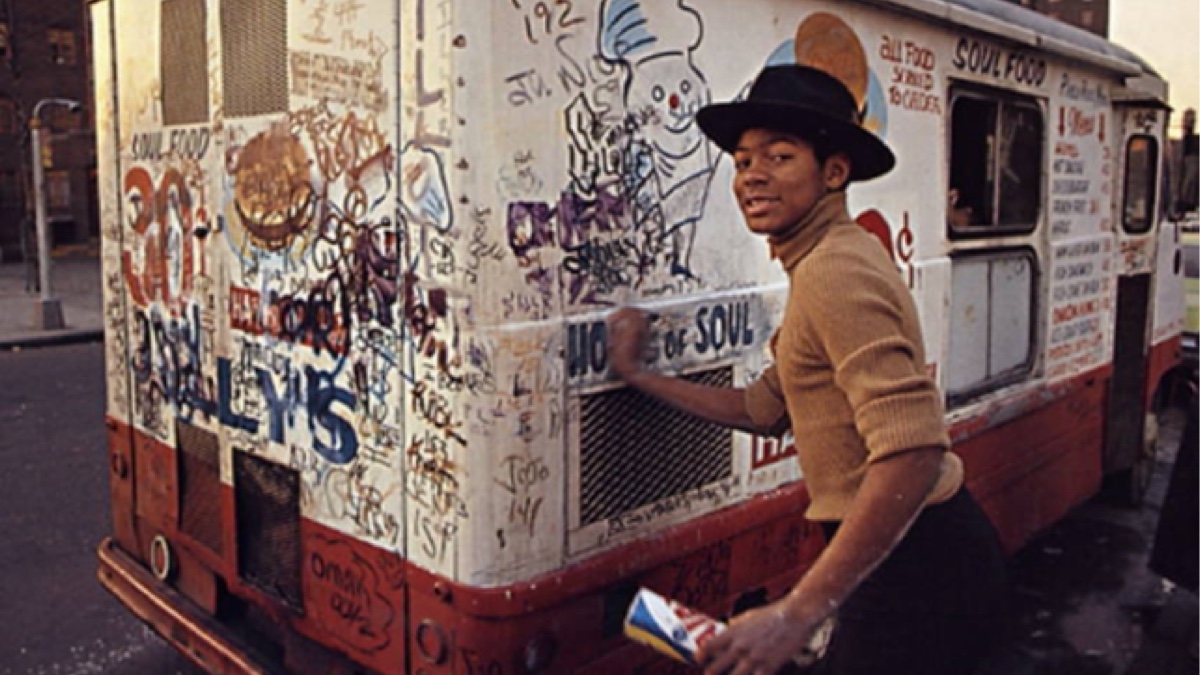

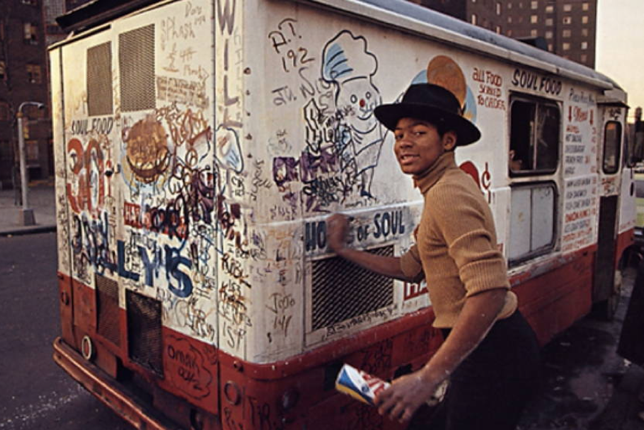

Basquiat

In 2017 graffiti artist Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work Untitled, sold for $110m at Sotheby’s in New York. The provocative enfant terrible of the 1980s became a pioneer of American Expressionism, due to his beginnings as a member of graffiti duo, SAMO (same old shit). Basquiat’s work is not aesthetically pleasing to the eye, but it isn’t intended to be. Although critics will regard the absence of grace as the main downfall of street art, it is exactly the purpose of the movement. Basquiat’s guileless skull intends to evoke the suffering and innocence of a young black man neglected by a racist society; not to brighten the walls of a community centre or alleyway.

Also in 2017, the enigmatic Banksy’s Balloon Girl was named Britain’s favorite artwork, beating the pastoral scenes of Constable’s 1821 painting, The Hay Wain. Outrage ensued amongst art aficionados; how could something that was spray painted beat a Romantic masterpiece?

Banksy

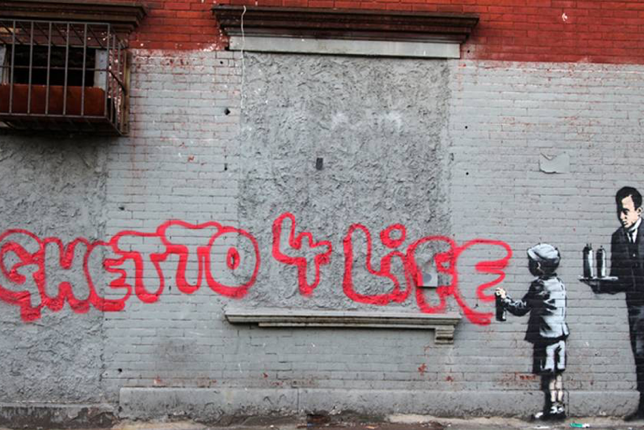

For a start, street artists like Banksy challenge the way we see privatised public spaces, where images and iconography are reserved solely for advertisement and road signs. It’s not only the subject matter of Banksy’s work that’s politically charged, but the placement of the piece is integral to its message. Ghetto for life was created in the Bronx; a neighbourhood with a large ethnic minority that has long felt the pressures of social and economic injustices. These values are often associated with the derogative term “ghetto”, which Banksy contrasts with a young middle-class boy being served a spray can on a silver platter.

To many non-Bronxites, this image is simply a powerful and humorous satire of street art’s increasing prominence in the esteemed world of fine art. However, when this piece was unveiled on the Melrose wall in the Bronx, it was met with fierce criticism from locals. According to Bronxites, Banksy’s piece only reinforced the cultural stereotypes their community had been trying to overcome for decades. A wound that ran especially deep coming from a white, western and now multi-millionaire accredited artist.

An open dialogue

Although Bronxites were upset by Banksy’s artwork, it did achieve what street art sets out to do: open up a dialogue between communities. This neighbourhood was the centre of international media, but not to report on the latest gang brawl or bloodshed, rather to give a platform to an otherwise dismissed community. Media outlets wanted to know how the work affected locals, resulting in individual voices finally being heard on what the Bronx actually means to Bronxites. Silenced and uncredited citizens were at last able to paint a vibrant and valuable depiction of their neighbourhood, revealing the beauty of a community usually shrouded by an impenetrable mist of preconceptions.

Creative expression

Street art is essential in our increasingly regulated communities, where CCTV, moving adverts and colossal billboards govern our lives. An absence of street art would only reinforce the idea that creative expression and art must also be monitored; ensuring it adheres to Big Brother’s ideal.

Emphasising street art’s importance is what online enterprise, Street Art Cities, does best. With such an extensive archive of international murals and works, viewers are able to appreciate works in the most far-flung corners of the world, at the touch of a button. Such initiatives make individuals more receptive to art in their communities, and the comprehensive maps guide users through either a virtual or physical tour of the area’s best murals. Online marketplace, Artsper, demystifies the process of acquiring works by disregarded urban artists, giving them a vital platform to not only exhibit but also sell their works. In placing street art on the same website as more traditional media such as ‘painting’ and ‘sculpture,’ the movement finally gets the much deserved credibility it lacks in the art world.

Although street art might not have the grandioseness of Romanticism, Artsper and Street Art Cities celebrate its ability to overcome barriers of class, gender, ethnicity and sexuality – which is a lot more than can be said for Constable’s The Hay Wain.

About Artsper

Founded in 2013, Artsper is an online marketplace for contemporary art. Partnering with 1,800 professional art galleries around the world, it makes discovering and acquiring art accessible to all.

Learn more