A Short Guide to BioArt

This week, Artsper examines BioArt, a phenomenon whose importance is constantly growing. While BioArt festivals are being organized in numerous museums around the world, this trend raises several questions: where is the border between art and science? Is it legitimate to use scientific methods in order to advance the creative process? We’ll try to find some answers to these questions.

Stelarc, Australian forerunner of bioart, summarizes, in one sentence, the ultimate goal of BioArt: bringing man to become his own work of art, by going beyond his limits, up to the point where he becomes a hybrid entity.

“We’ll die when we unplug the computers that keep us alive.”

Bioart is difficult to apprehend, because it takes a different form depending on each artist. That’s why it’s easier to study the phenomenon on a case-by-case basis.

In 2010, French artist Marion Laval-Jeantet , with the help of Benoit Mangin, injected herself a significant quantity of horse blood. Bio-technological methods, used exclusively for science until recently, become a means of expression for artists. May the Horse Live in Me transformed Marion in a Centaur, half-woman and half-horse. During the performance, she got a fever (a horse fever, obviously), and she could barely walk, perched on pair of prostheses imitating horse hooves. During the weeks following the injection, the artist didn’t get more than four hours of sleep a night, felt like she had an unusual physical strength, totally unlikely as she has a petite figure, and a gargantuan appetite. Also, she panicked every time someone approached her from behind. These are typically the reactions of a horse. Her decision involved huge risks, as it is well known that in any transfusion, and even more so when two different species are involved, the risk of anaphylactic shock that can cause death is extremely high. Beyond the almost mythological aspect of the performance, the artist wanted to emphasize the place that animals hold within our societies, by substituting herself to the animal, and by going beyond the human perception.

May the horse live in me, 2010, Kapelica Gallery, Ljubljana, Slovenia

Bioart is, in its essence, unsettling. The differences between nature, technical methods, the organic and death are totally blurred.

Today, bioart does not fit any of the well-established categories of the international art market. But anyways, it is not created to be accepted by the market. These two entities are mutually exclusive. The reason is quite understandable: most of the time, it is not about producing objects, but about exposing ephemeral bio-technological processes that have actually a clear goal: merely that of legitimizing the fact that they exist. To put it more simply, bioart cannot possibly last, as its main “material”, the human, is doomed to die. It is an art form that doesn’t last.

The preparatory processes are often long and complicated. May the Horse Live in Me required years of experiments in order to ensure that the transfusion is done in the best possible conditions. If you have doubts, and you have every right to have them, you must know that bio-artists are convinced of the relevance of their actions, and think that bioart will be recognized as an independent movement in the following years.

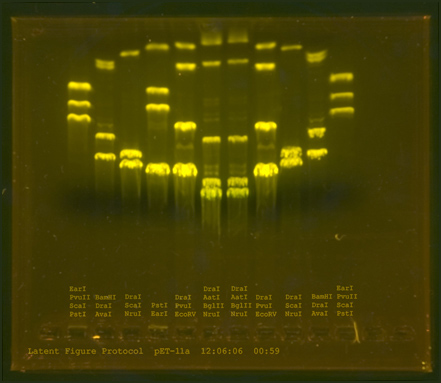

Artist Paul Vanouse has been working, since the early 90s, on genetic patterns. It is commonly accepted that this pattern has absolute integrity, and that genes are non-modifiable. Paul Vanouse calls into question these certainties with his DNA manipulations. His a posteriori and artistic construction of the DNA completely reverses the vision we have of these issues. The artist can make any profile, as a recipe he would make from a few given ingredients.

Latent Figure Protocol, 2006

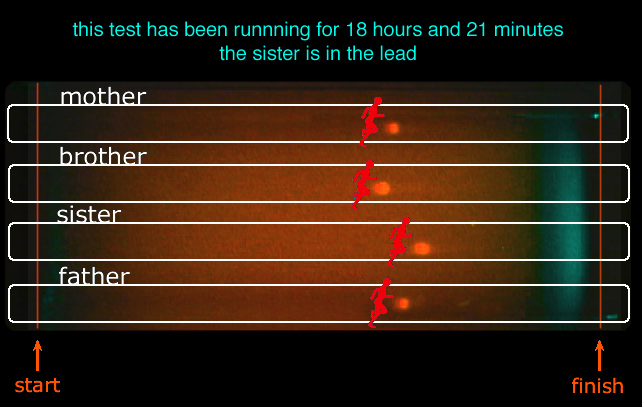

If he uses science in his practice, it is first of all in order to evoke the scary but legitimate possibility of a resurgence of eugenics (the Nazi ideology). Genetic racism, a whole new form of discrimination, is not far from these experiments. In his work Relative Velocity Inscription Device, Paul Vanouse, who comes from a multi ethnic family, organizes a race between the genes responsible for the skin color between his sister, his brother, his parents and himself. That’s fun, but terrifying.

Relative Velocity Inscription Device

The artists working in the laboratories can be compared to the war correspondents, mid-way between two worlds, trying to raise awareness about the blindness of the media when it comes to science. Bioart lets us realize to which extent humans can be manipulated and modified.

Joe Davis, a forerunner of bioart, the man with a wooden leg, works in close collaboration with the prestigious MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology). He has manufactured bacterial radio circuits and bacterial electronics. Never short of ideas, Joe Davis militated, in the ‘70s, for sending art in space, with Poetica Vaginal, a sound signal that transcribed vaginal contractions. For him, the artist’s first duty is that of opening a window on the world, and a window is interesting if opened on something completely unknown. In this direction, art and science are both advancing toward a common goal.

Under the guise of humor, irony and provocation, bio-artists have a thorough knowledge of fields such as molecular biology or physics. If it were to connect them to a current, that would be the humanism of the Renaissance. Rigorous, with mathematicians’ minds, they can be placed in the direct lineage of Leonardo Da Vinci.

Japanese artist Jun Takita proposes a different approach. Recently, he has made a 3D model of his brain that he has covered in a genetically modified fluorescent foam. By using their bodies as their main material, artists are trying to learn things subjectively, and to make general knowledge progress. Our existence is not reduced to a genetic body. The genetic body is merely the product of evolution, and the starting point for an evolution to come, one that will be shaped by men, with an almost theological dimension. Men build extensions for themselves in the form of technical and biological innovations, freed from their carnal shell.

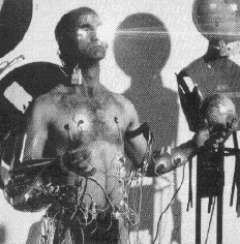

Australian artist Stelarc considers the body to be obsolete and inadequate in its current form. For him, the issue is not that of “building” a perfect body (so we get rid of the danger represented by eugenics), but to explore different anatomical “architectures”. In his Body Hacking series, the artist changes the body through prostheses, which makes it possible to envision its development beyond today’s borders.

Our body has empty spaces that could, in all likelihood, accommodate technology. Bioart would become intended for a physiological private space (the inside of our stomachs for example). Veritable cyborgs, pure receptacles that escape death and even birth, through cloning… If there was no more birth and no death, how could we define our existence then?

Does this ear implanted in the arm of the artist make you cringe? The purpose of it is not that of forcing the body go through a painful experience (even if some of Stelarc’s happenings might make us doubt that). It is first and foremost a challenge for the artist, that of having access to modern technology, and seeing its results.

Bio-artists are generally trying to make visible things that are not accessible to us. The lack of public interest doesn’t mean that the performance is not valid, but most of them remain completely confidential, and conduct their researches by themselves. We have to admit that for many artists, narcissism plays quite a big role when it comes to this kind of experiments, whether it be for introspection, or to make their body accessible to everyone, by amplifying it and by offering complete access to it. The inside of the body is no longer a mystery.

As Frankenstein, men carry within them the original wound of not being able to create nature by themselves. Bioart allows artists to become God. But the risks are huge. Bio-technological methods come at very high costs: these artists get almost no recognition, their art doesn’t sell, and even showing their work is almost impossible.

Which means the freedom of creation is complete.

About Artsper

Founded in 2013, Artsper is an online marketplace for contemporary art. Partnering with 1,800 professional art galleries around the world, it makes discovering and acquiring art accessible to all.

Learn more