In the Land of Soviet Art

From 20th March 2019 to 1st July 2019 the Grand Palais will pay homage to Soviet art with its exhibition, “RED : Art and utopia in the land of Soviets”. Artsper takes you back in time to the heart of Soviet art, so you can discover more about this turbulent period in history.

While the Soviet regime undoubtedly changed the course of history it also turned the art world upside down, resulting in a distinctive art movement rich in radical ideologies. The regime’s goal was to propose an alternative utopia to the world; one that had never been seen before. As a result, a new art movement was born which offered valuable insight into this historical period, and it continued throughout the regime from its very beginning to its disgraced end. We can therefore draw parallels between the movement’s evolution and the leaders of the Soviet bloc: Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev and Gorbachev, were each symbolic during their reign in the USSR.

Art’s Contribution to Lenin’s Revolutionary Utopia (1917- 1924)

Although it was the Russian Empire that allowed the Russian avant-garde to advance, its popularity still continued even after The October Revolution. The Bolshevik Revolution transformed art and artists: it rendered art accessible to the proletariats and connected art to the new life promised by the Revolution. Artists such as Rodchenko and Klutsis turned towards new forms of art, including graphic art, design and architecture in order to oppose the “old order”. Artists were relatively unrestrained during the first years of the Soviet Union, however many others escaped the regime due to their opposition to the Bolshevik government. Although Lenin prefered more traditional art to newer movements such as Futurism or Expressionism, he remained supportive of the developing artistic scene. He saw the popularity of the arts as an opportunity for making his policies accessible to the masses.

Socialist Realism: Stalin’s Political Instrument (1924- 1953)

Official Art: The Orburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was quick to restrict literary and artistic organisations. This permitted it to create instead, a sole union of writers and artists that adhered to and disseminated the regime’s ideas.

This was the beginning of Socialist Realism, which was the only official art movement of the Soviet Union. Its goal was to use realist styles that depicted the “social reality” of the working class, labourers and soldiers. There were severe repercussions for those that did not comply, so talented artists like Deïneka, Pimenov and Samokhvalov, took on board this movement regardless of whether they supported the Socialist regime or not.

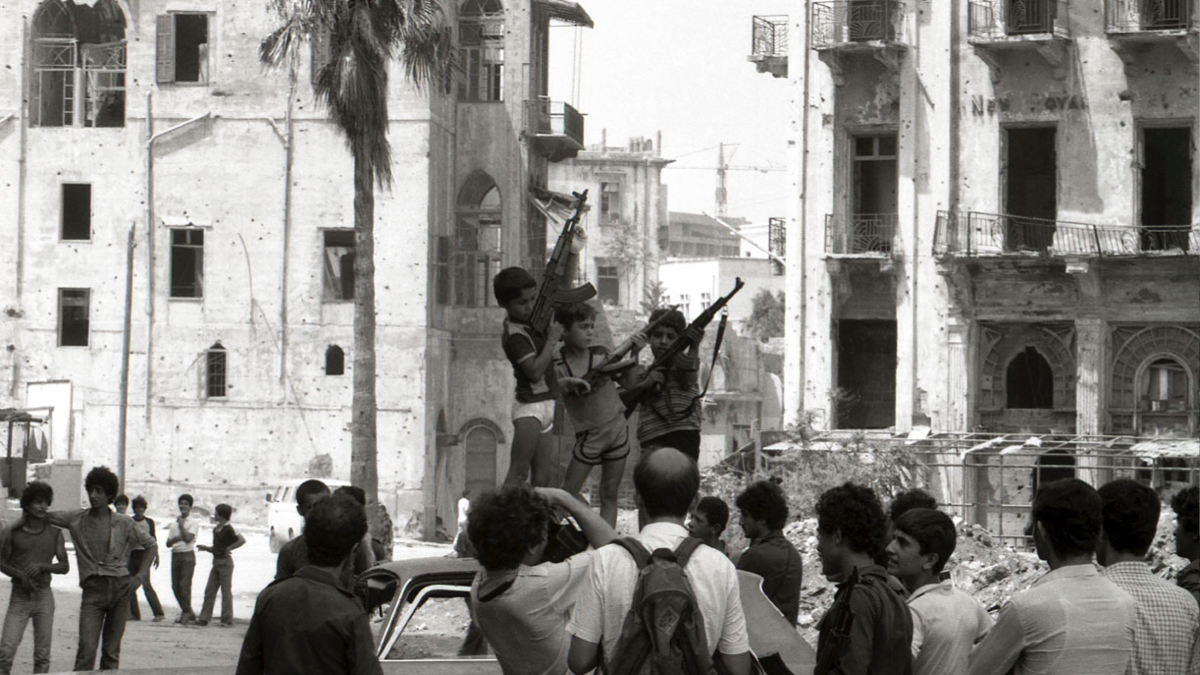

Dissident Art: Stalin’s communism had no enemies, or rather it didn’t tolerate them; those who were opposed to it were quickly removed. This drastic measure also applied to artists, where all art movements other than Socialist Realism were heavily controlled. All dissident creatives were censored, and not conforming to censorship was punishable by imprisonment in the terrible Gulag labour camps. Art students were even taken prisoner in Siberian camps, like Ülo Sooster, who later became an important member of the Soviet Nonconformist Art movement in Moscow.

Soviet Nonconformist Art under Khrushchev and Brezhnev (1953-1985)

After Stalin’s death and under the new rule of Khrushchev, the USSR experienced a period of “De-Stalinization”. As a result, artists felt more liberated and less afraid of the consequences of the their creations. Even though no official political change had occurred, artists regained the confidence to experiment with their art. However, artistic politics were far from being liberal. Although Khrushchev used art as his “showcase” of East Berlin, he also aggressively criticised certain avant-garde artists. During an exhibition at the Moscow Manege in 1962, he branded various abstract works, included those by Ernst Neizvestny, as nonconformist “degenerate art”. Despite this, the second wave of the Russian avant-garde was in the making, as artists grew increasingly defiant of USSR rules.

Rule Under Gorbachev: from Artistic Liberty to the End of the Movement (1985-1991)

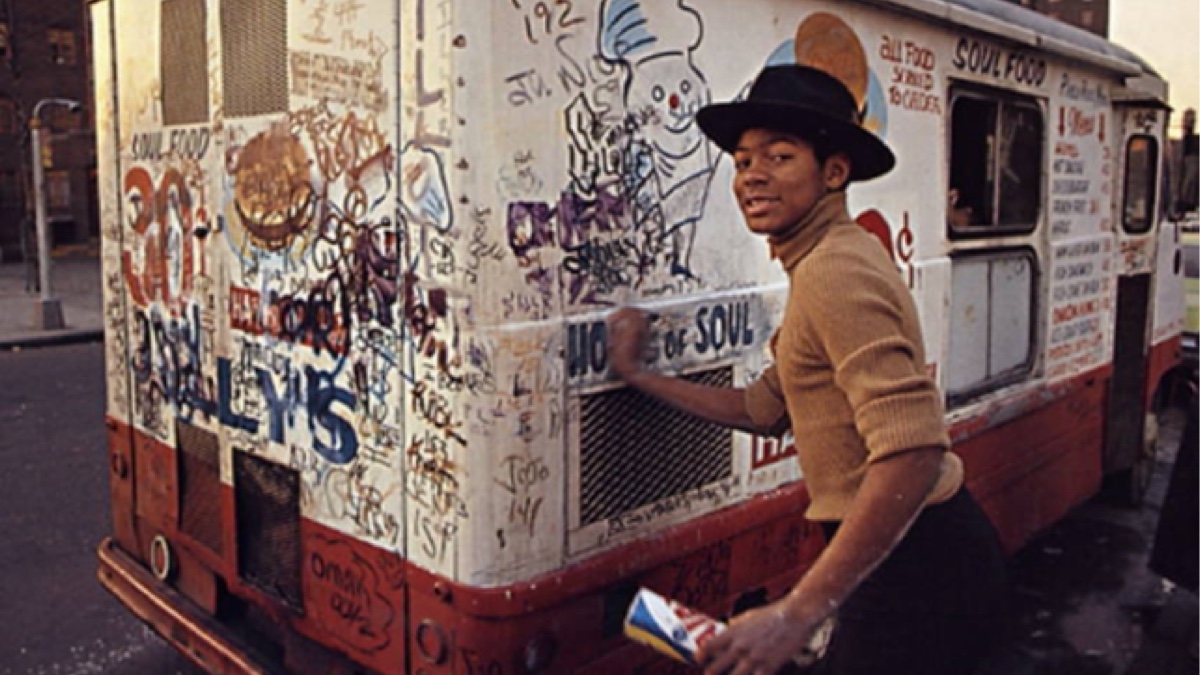

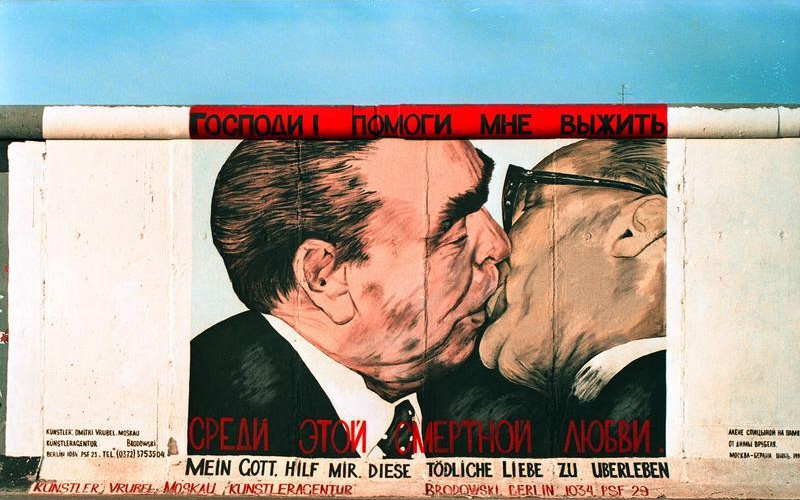

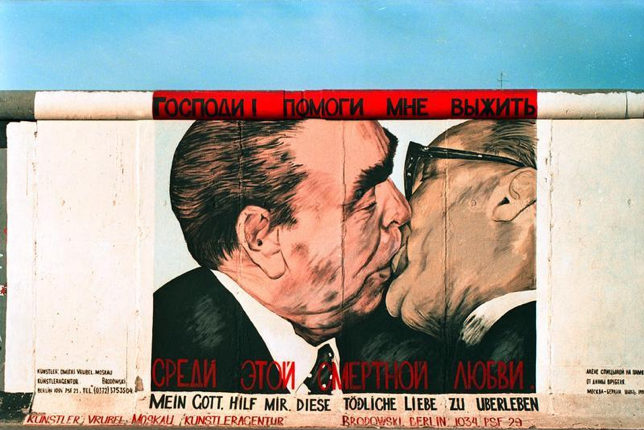

In 1985, Gorbachev’s political policies “Perestroika” and “Glasnost” prevented the authorities from imposing restrictions on artists. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, artists were no longer reliant on the Communist State to create artworks. This freedom to create without fear was evident in Russian street artist Dmitri Vrubel’s works. In 1990 he completed his famous piece, My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love also known as The Fraternal Kiss, that decorates a section of the Berlin Wall. This deliberately provocative work was recreated from a photo taken 10 years earlier, that captured Brezhnev and GDR leader Erich Honeckerin in a fraternal embrace. Through this work, Vrubel portrays the diminishing control of the Soviet Union and the liberation of art. However, as the USSR declined so did nonconformist art, as its existence served to fight against this disgraced regime.

About Artsper

Founded in 2013, Artsper is an online marketplace for contemporary art. Partnering with 1,800 professional art galleries around the world, it makes discovering and acquiring art accessible to all.

Learn more