10 Things to Know about Kasimir Malevich

“Suprematism” derives from the Latin word “supremus”, which means “superior”. Kasimir Malevich’s life certainly began in a position of “superiority,” being the eldest of a family of 14 children of whom only eight survived. His love of Ukrainian embroidery and folk art paved the way for his creativity at an early age, and he later whetted his artistic appetite at the Moscow School of Painting. Surrounded by some of the most talented figures in early 20th century art, he fraternized with the elite of the Eastern avant-garde: Vladmir Taltin, Sonya Delaunay, Vladim Meller and Aleksander Archipenko. Often referred to as an enigma, Malevich was a revolutionary, even during the Russian Revolution; he disrupted conventional thinking and exposed a new experimental understanding of reality.

Artsper invites you to discover 10 facts about the man behind the infinite Black Square.

#1 Malevich’s Black Square is quite simply a black square

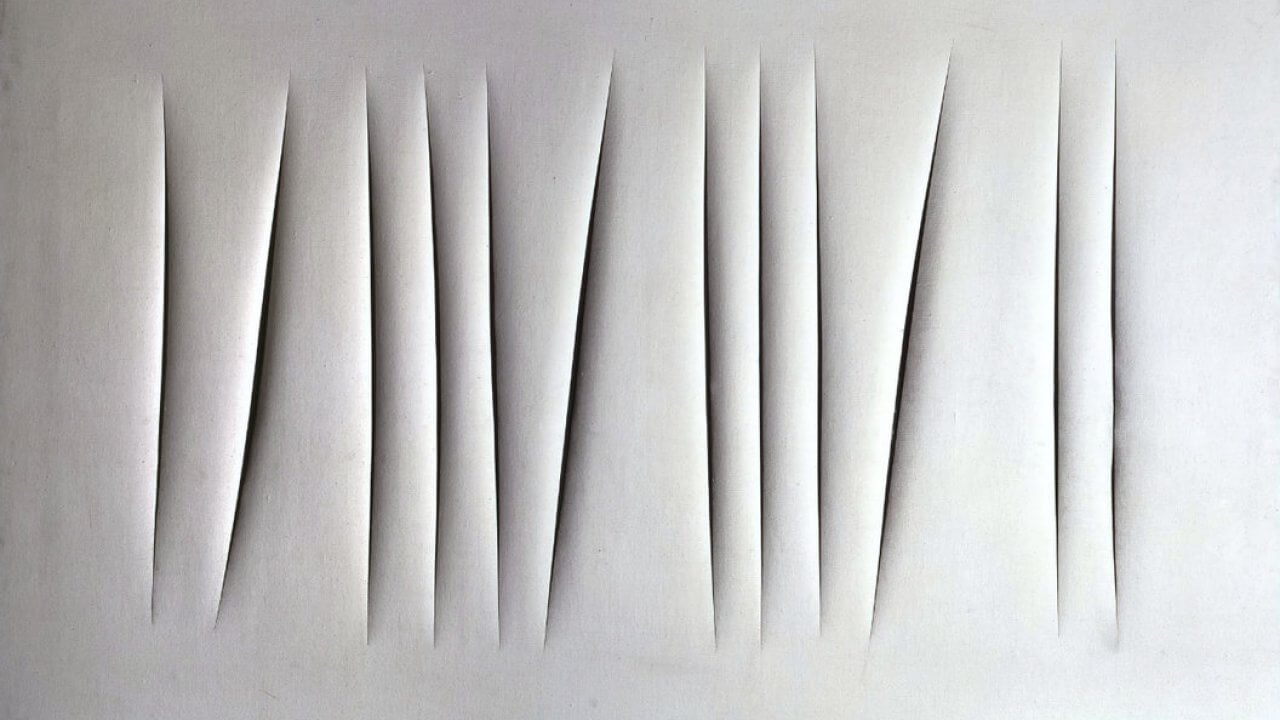

Malevich’s painting rejects conservative art values and does not seek to embody reality or a natural image: it simply serves to convey an abyss of darkness. No attempt has been made to alter the painting’s aesthetic for the viewer’s pleasure, and Malevich hasn’t intended a profound meaning to be deciphered from the obscurity. Other than evidence of wear and age, Malevich’s painting remains a black square created purely as “art for art’s sake.”

#2 He invented the term “Suprematism”

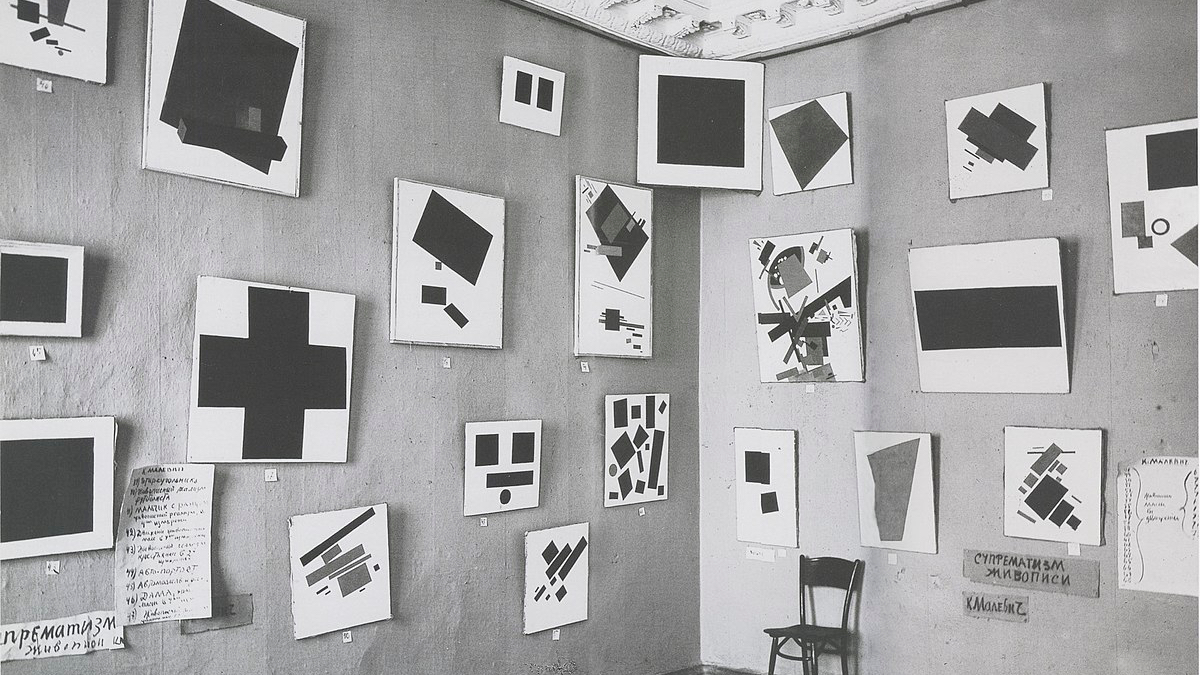

Malevich developed a branch of abstraction in 1913, which consisted of simplified geometric forms and a diluted colour palette. Circles, squares, lines and rectangles drift across a white void like fleeting thoughts in the mind. His canvas forms a Suprematist utopia and liberates “art from the dead weight of the world.” Suprematism was a central movement to the Russian avant-garde; flourishing with the revolution and withering after Stalin’s rise to power.

#3 He was a prolific writer

Malevich expressed himself through both visual and written language, using his theoretical principles of Suprematism to decode the new state order. His manuscripts include: From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism (1915) and The Non-Objective World; The Manifesto of Suprematism (1926). Malevich encouraged the distribution of avant-garde art for its purpose and ability to guide people to a new spirituality.

#4 He was arrested due to his political ideologies

In 1930, Malevich was arrested and questioned, and his fellow artists and creatives burnt his manuscripts and essays as a precaution to protect him.

#5 His works are amongst the most forged in the world

In 2017, Malevich’s Black Rectangle and Red Square (1915), was revealed as forgery in the Dusseldorf state collection. This work was acquired by the Dusseldorf public collection in 2014, and upon finding out about its lack of authenticity, analyses of the work were commissioned. Detailed studies revealed the piece couldn’t have been produced before 1955, forty years after its claimed creation.

#6 He took over Marc Chagall’s job as director of the art university in Vitebsk

In 1917, during the Bolshevik Revolution, Malevich was employed as a teacher by the faculty of arts at the university in Vitebsk. This was the same year Marc Chagall was declared the “Commissar of the Arts for Vitebsk.” However, due to the damage and poverty that shrouded post-war Russia, Chagall left for Paris and Malevich assumed his position.

#7 If it wasn’t for Georges Costakis and Nikolai Khardzhiev, most of Malevich’s works would have been destroyed

George Costakis and Nikolai Khardzhiev were art collectors and Malevich-aficionados, who secretly tracked down and collected the artist’s works. After Malevich’s arrest, his works were confiscated and destroyed due to his radical theories. Disseminated across Europe, the collectors’ efforts to preserve these incredible works were paramount to the survival of Malevich’s legacy.

#8 Despite being a “Russian” artist he considered himself Polish.

Born in current-day Ukraine, his parents were ethnic Poles and Malevich held a profound attachment to the country. When travelling to France, Malevich claimed his nationality as Polish on his visa application, and would even sign his name using the Polish spelling, Kazimierz Malewicz.

#9 One of Malevich’s masterpieces was actually made by his student

The Portrait of Elizaveta Yakvleva was recently discovered to have been made by Malevich’s former student, Maria Dzhagubova. Detailed analyses of the painting and numerous x-rays, indicate the signature was started by Malevich but finished by somebody else. It is suggested Dzhugubova’s name was rubbed out and the work quickly appropriated by a white male artist; a paragon for the woman artist’s struggle in the art world.

#10 His grave is marked with a black square

On the 15th May 1935, Malevich died aged fifty-seven. His fellow artists, creatives, intellectuals and friends, distinguished his grave with a black square. Emblematic of both his life and death, Malevich’s Black Square was also mounted above his bed where he lay dying.

About Artsper

Founded in 2013, Artsper is an online marketplace for contemporary art. Partnering with 1,800 professional art galleries around the world, it makes discovering and acquiring art accessible to all.

Learn more