Understanding German Expressionism

From the 6th of March to the 17th of June 2019, the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris is honouring to two major artists of German expressionism, Franz Marc and August Macke, who both died on the front lines in 1914. In preparation for the exhibition, here’s a brief overview German expressionism. The movement can be divided into two distinctive groups: Die Brücke et Der Blaue Reiter. Despite their different approaches, these two movements are often amalgamated and simplistically encompassed into a single German expressionist movement.

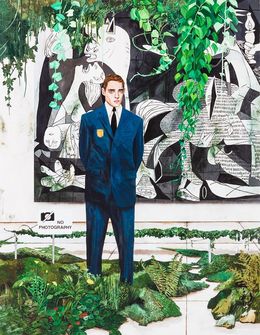

Die Brücke

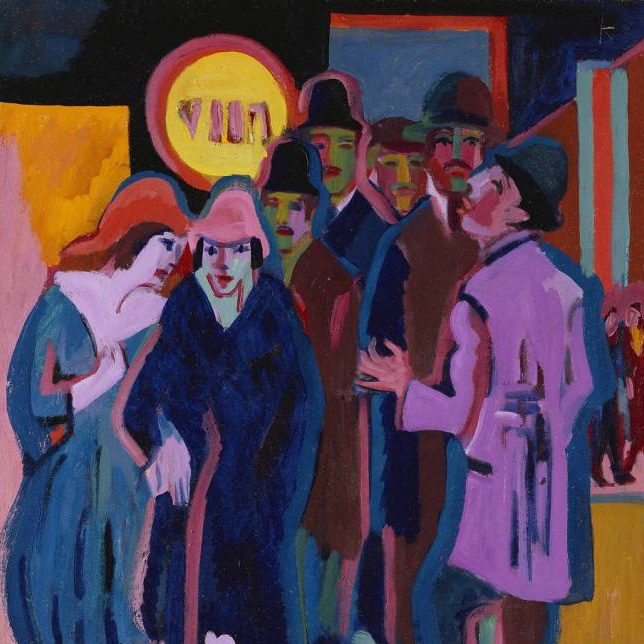

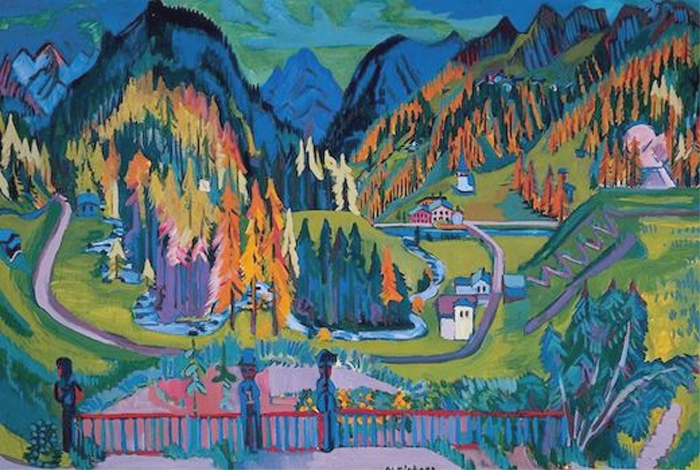

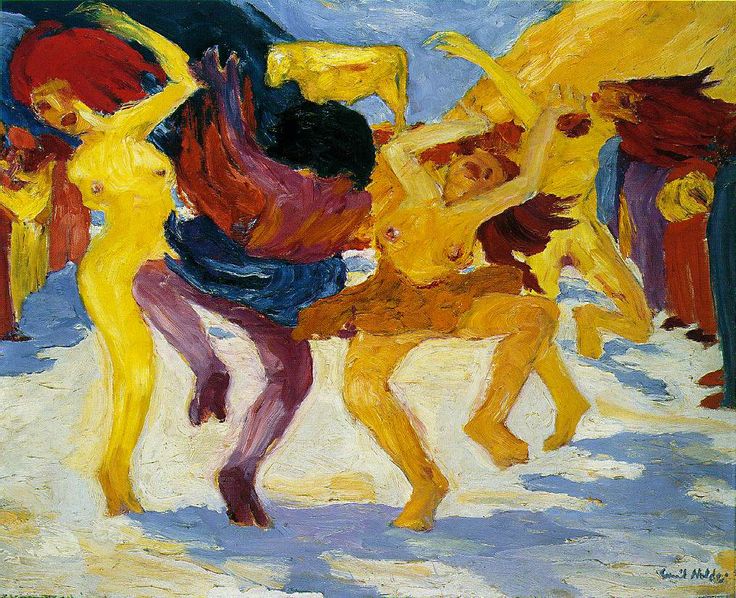

Die Brücke (The Bridge) was formed in 1905 in Dresden. It claimed an emotional sensitivity, away from any intellectual essence. Working with their instinct, artists expressed their uneasiness towards German society that was sinking in a latent collapse. Regarded as “degenerates” by the increasingly popular socio-nationalist party, the artists powerlessly witnessed the rise of this extremist group. The artists who spearheaded the movement were the artists Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Erich Heckel.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was probably the most important figure of the Die Brücke movement. Through an exalted hypersensitivity and the use of strange shapes and bright colours, Kirchner evoked Berlin’s urban transformation.

Emil Nolde was also a central painter of the movement. Strongly influenced by Vincent Van Gogh, he drew his inspiration from primitivism and the myth of the “savage”. His work demonstrates a clear psychological atmosphere, as well as an omnipresent and romantic nature.

Der Blaue Reiter

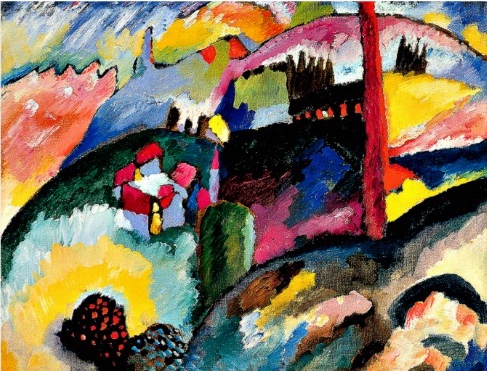

Der Blaue Reiter appeared after Die Brücke, and was an artistic movement born out of an intellectual reflection of thinkers and philosophers. These intellectuals interrogated the artwork’s boundaries and its authority. This movement was rather theoretical and owed its origins to Gesamtkunstwerk’s German romantic culture as well as elements of the Die Brücke movement. This short expressionist wave lasted from 1912 to 1914. It’s key artists included Vassily Kandinsky, Gabriele Munter, Franz Marc, August Macke, and Alexej von Jawensky.

In the Preface of the “Der Blaue Reiter Almanac”, Vassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc described the artistic movement as follows: “Our first and most important goal is to reflect artistic events directly connected with this change and the facts needed to shed light on these events, even in other fields of the spiritual life. Therefore, the reader will find works in our series that bear an inner relationship to one another in the aforementioned context, although they may appear unrelated on the surface.”

And concerning the name of the movement “The Blue Rider,” in an era where the “-isms” (fauvism, cubism, expressionism, futurism…) abounded, Kandinsky explained: “We [Franz Marc & Kandinsky] thought up the name while sitting at a cafe… Both of us were fond of blue things, Franz Marc of blue horses, and I of blue riders. So the title suggested itself.”

Differences and Similarities

There are clear geographical differences between the two movements. Die Brücke was more affiliated with Dresden and Berlin, while Der Blaue was more strongly connected to Munich.

However, they did have certain visual elements in common. First of all, they both participated in the resumption of the bestiary aesthetic, and the use of lurid colours, almost garish or gaudy. This aesthetic recalled fauvism, with a figurative style using exaggerated distortions. Paradoxically, Blaue Reiter’s paintings used a range of powerful and expressive colours, which granted it a sensitivity more exacerbated than Die Brücke’s. Die Brücke artists were of a rationality relative to their artworks, where shapes and figures are more distorted.

Unfortunately, the horrors of the First World War took away the artists Franz Marc and August Mack, while Kandinsky and Jawlensky are forced to go back to Russia. The historical context put an end to the activities of these early 20th-century avant-garde artistic movements.

About Artsper

Founded in 2013, Artsper is an online marketplace for contemporary art. Partnering with 1,800 professional art galleries around the world, it makes discovering and acquiring art accessible to all.

Learn more